I finally finished the shelves for the cabinet, so it could receive some toys and help to keep a tidy room.

Now there is just one obstacle left.

The cabinet is too large to be carried up our staircase..

So since I have (more or less) sworn a solemn oath, that this cabinet shall be mounted in our youngest sons room.

The most straightforward solution is to disassemble the entire cabinet (which is probably between 80 - 100 years old).

So Now I have a partly disassembled cabinet in my workshop, and a new job putting it back together and applying some new paint on it before it can be mounted.

A little sympathy would be appreciated :-)

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Make Two of Everything

|

| Trevor the Mallet and Travis |

I noticed early on in my hobby, that when I finished a project, I often felt like next time I could do it better, faster, or with something different.

Usually, I wouldn't do it again.

This could be a mistake in some cases. I think that what is really going on is that my project was actually a prototype. Even better, you could call it the first prototype.

A good example in my recent work was with a recent project, the diagonal Chinese cross puzzle. The first one took me two days. The second one, which was arguably better, took two hours. I think I would even like to build a third, as perhaps I think I could improve the fit. Or at least try something.

|

| Diagonal Chinese Crosses |

I noticed the exact same thing when building try squares a couple weeks ago. The first wasn't too square, had some gappy joints and the design didn't give the same effect that I had envisioned. The second was much nicer, and I adjusted the design a bit that looked much better. The last one had virtually perfect joints and the design change here made it even easier to build.

The mallets used a completely different joint to attach the head, but I got some good practice in cutting stopped chamfers on the handle using only a chisel. The second mallet (Travis) turned out a lot cleaner than the first (Trevor).

What's the moral of this story? I think you know. Practice makes perfect. If you can, make your builds in multiples. If it is a bigger project than the ones I have listed, you may consider building two consecutively. If you do a joint on one piece, the second time you do it for the other will be more successful because you will have practiced it. Faster, smoother, better. If the joint turns out not to be an ideal choice, there is nothing saying you can't do it different the second time.

I am preparing to build another dining table, for our own home. Last year I built a dining table as a gift for my in-laws. The point of that build was that I had never built a dining table before. They needed a small table, and everything about this one was intended to prepare me for my upcoming table build. My next table will be a bit bigger, but I learned a lot with the first build.

- hand cut mortises are not difficult.

- hand cut tenons get better and more accurate the more you practice them.

- one should not only test fit the mortise/tenon for each individual joint, one should test them all together before glue up. Yeah....

You shouldn't have regrets in woodworking. Rather than thinking, "next time it will be better," do it!

Monday, January 28, 2013

Double Sliding Dovetail Mallet - Basic Tools Project

I alway's thought the mallet Roy Underhill makes with the double, sliding dovetails was super cool. Maybe someday I will make one, it looks like a fun project.

However I already have a mongo mallet named Trevor. I intended to make a general-purpose mallet. When I finished it, it was obvious that this was a badass mallet ideally suited for mortise chopping.

What I really needed was something with a bit more finesse. Trevor, although a really cool mallet, was built to make my joints come apart after a day of chopping dovetails.

So, in keeping with my Basic Tool Kit project theme, I made another one using only a few tools: A jack plane, a ryobi saw, marking gauge, square, marking knife and a 3/4" chisel.

I noticed that Bob Rozaieski at the Logan Cabinet Shoppe has a lightweight mallet made of two contrasting pieces of 4/4 lumber. I thought I would do the same, and here is what I came up with:

This mallet has a sliding dovetail, but only one. I got the idea from Fairham's book. He describes this joint as a good puzzle joint for practice, but with no practical use. I decided to make it into a practical use.

Once again, I used Honduran mahogany scraps and a leftover bit of walnut I had rolling around. Figured it would look neat that it was made to match Trevor.

My wife came up with the name Trevor for the big mallet. I was thinking this one should have a name, too. Unfortunately, the first thing that popped into my mind was "I bet The Frau would come up with something like Travis for this one."

So, that's it. Trevor the Mallet, and his little brother, Travis.

However I already have a mongo mallet named Trevor. I intended to make a general-purpose mallet. When I finished it, it was obvious that this was a badass mallet ideally suited for mortise chopping.

What I really needed was something with a bit more finesse. Trevor, although a really cool mallet, was built to make my joints come apart after a day of chopping dovetails.

So, in keeping with my Basic Tool Kit project theme, I made another one using only a few tools: A jack plane, a ryobi saw, marking gauge, square, marking knife and a 3/4" chisel.

I noticed that Bob Rozaieski at the Logan Cabinet Shoppe has a lightweight mallet made of two contrasting pieces of 4/4 lumber. I thought I would do the same, and here is what I came up with:

|

| My new light weight mallet. |

Once again, I used Honduran mahogany scraps and a leftover bit of walnut I had rolling around. Figured it would look neat that it was made to match Trevor.

My wife came up with the name Trevor for the big mallet. I was thinking this one should have a name, too. Unfortunately, the first thing that popped into my mind was "I bet The Frau would come up with something like Travis for this one."

So, that's it. Trevor the Mallet, and his little brother, Travis.

Sunday, January 27, 2013

Priorities in woodworking

It often amazes me, how long time it takes for me to complete a project.

I don't believe that I am slower than the average woodworker, but maybe the problem is the priorities when it come to woodworking .

The majority of my projects have some degree of woodworking or carpenter work in them. But eventhough I have a pretty good idea of what I would like to complete first, things don't always end that way.

Various things tend to get in the way of my projects, some of them beyound my control.

Of the bigger projects; I started installing a sawmill which went along rather smoothly untill the winter suddenly appeared with frost etc. That sort of ended the posibilities of casting concrete until we had a period above freezing point again.

I then started the workbench which made some OK progress untill I had to produce some sawdust for the horses, so they had something on the floor in the stable.

That took about a day.

Then my wife urged me to finish the cabinet for our youngest sons room. So I had to process some wood for making shelves and a vertical divider as well. This project clearly overrules the other projects.

So the result is, that I have a over cluttered (messy) workshop.

On top of all this, our middle son has rediscovered his interest in woodworking, and have made a list of things he wants to build..

Right now he is making a fish shaped trivet, and off course needs a little assistance now and then.

I don't believe that I am slower than the average woodworker, but maybe the problem is the priorities when it come to woodworking .

The majority of my projects have some degree of woodworking or carpenter work in them. But eventhough I have a pretty good idea of what I would like to complete first, things don't always end that way.

Various things tend to get in the way of my projects, some of them beyound my control.

Of the bigger projects; I started installing a sawmill which went along rather smoothly untill the winter suddenly appeared with frost etc. That sort of ended the posibilities of casting concrete until we had a period above freezing point again.

I then started the workbench which made some OK progress untill I had to produce some sawdust for the horses, so they had something on the floor in the stable.

That took about a day.

Then my wife urged me to finish the cabinet for our youngest sons room. So I had to process some wood for making shelves and a vertical divider as well. This project clearly overrules the other projects.

So the result is, that I have a over cluttered (messy) workshop.

On top of all this, our middle son has rediscovered his interest in woodworking, and have made a list of things he wants to build..

Right now he is making a fish shaped trivet, and off course needs a little assistance now and then.

The cabinet (2nd hand)

The first glue up of four shelves for the cabinet. At least I get to use my new workbench. (the tenoning jig was put there to add some weight)

So how about your projects? Do they just slide through, or are there similar obstacles that pass them on the priority list? (Work doesn't count like an obstacle).

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Shoulder vise installation

Here is the sandwich construction of the new shoulder vise. It is made from an old shoulder vise I had on another old workbench. I'll try to reuse the drilled hole for a reinforcement threaded rod.

Here is the glue up on the bench itself. As a side note, I have left the kerosene heater running, in order to keep the temperature so that the glue will actually work.

The pressure plate is being made from a piece of exotic wood (I think it is mahogany of some kind, I bought 0.5 cbm leftover from the production of windows etc.) I chose it due to the hardness, so it wouldn't get damaged by the spindle pressing directly on the backside of it.

I cheated and used the table saw.

More cheating for dressing the mahogany to the desired thickness and to remove a slight twist.

The glue up of the pressure plate and the "anti tilt stick". Since it is mahogany I have added glue to both sides of the joint.

I drilled four holes for screws to hold it together, but probably due to the aforementioned cheating, the 4 mm brad point drill broke inside one of the holes. So I had to settle for 75% holding power..

Here the pressure plate, anti tilt stick have been glued together. The stop block that will keep the assembly in place is ready to recieve the screws.

Here is the first test of holding a stick of wood. I couldn't figure out how to rotate the picture.

The plan is to install a threaded rod (12 mm) to prevent the screw of the vise to burst the glue up of the shoulder vise.

Monday, January 21, 2013

Diagonal Chinese Cross - BTK Project with VIDEO

An alternative title is:

Fun With Drywall Screws

Not long ago I listed a few of my favorite woodworking books. In this list was this one:

Ever since I read this book I couldn't wait to try some of the wooden puzzles listed in the back.

This was a brilliant project, that reinforces some basic fundamental skills such as squaring stock super-accurately, paring with a chisel, and layout by eye.

The book says you should use a stick of wood 1/2" square and cut it to 2 1/8" long pieces. I wasn't sure how this was going to work, so I went through the trouble of sawing some 3/4" stock down to 1/2" to make sure it would turn out.

As you'll see in the video, you can't really measure the angle, so you are welcome to make this puzzle any size you want. The pieces should be at least 1/2" longer than twice the diagonal of the endgrain (watch the video, and you'll understand what I mean and why).

I found it helpful to use drywall screws to secure a few bits of scrap onto my bench hook. This facilitates holding the small pieces so you can work on the diagonals.

Please be aware, there are a lot of ways to seriously injure yourself while doing this project. It only takes a small toolkit (jack plane, marking gauge, crosscut saw, and a large-ish chisel - 3/4" or so), but with these small pieces you might be tempted to secure them with your hands. Please do not let any body part get in front of the leading edge of your chisel.

Moving on, the first one I did in walnut turned out well. I just put some wax on the pieces for a finish. Fairham leaves you to figure out the solution to put it together yourself, which took me about a half hour. I got the impression that it was a bit loose and sloppy, as as soon as I touched it the darned thing fell apart again.

The second one (this time in cherry finished with boiled linseed oil) I chose to leave all of my cuts well inside the lines, hoping that it would cinch up tight. WRONG!

This made it even sloppier and looser, to the point that it wouldn't go together. I opened the joints up a bit, and it held together, but about like the first one. I did find out that once it is together, if you press all of the pieces together, then it stays fairly tight. Perhaps this is the way it is supposed to be.

Perhaps one of you knows the intricacies of the construction of this puzzle? In the meantime, I think I'll leave these on my desk and watch the faces of my visitors as the puzzle disintegrates as soon as they touch it.

Fun With Drywall Screws

|

| This was a really fun project. |

Not long ago I listed a few of my favorite woodworking books. In this list was this one:

|

| Fantastic book on Joine |

- Music: Jig of Slurs. Dublin Reel - Merry Blacksmith. The Mountain Road (Sláinte) / CC BY-SA 3.0

This was a brilliant project, that reinforces some basic fundamental skills such as squaring stock super-accurately, paring with a chisel, and layout by eye.

The book says you should use a stick of wood 1/2" square and cut it to 2 1/8" long pieces. I wasn't sure how this was going to work, so I went through the trouble of sawing some 3/4" stock down to 1/2" to make sure it would turn out.

As you'll see in the video, you can't really measure the angle, so you are welcome to make this puzzle any size you want. The pieces should be at least 1/2" longer than twice the diagonal of the endgrain (watch the video, and you'll understand what I mean and why).

I found it helpful to use drywall screws to secure a few bits of scrap onto my bench hook. This facilitates holding the small pieces so you can work on the diagonals.

Please be aware, there are a lot of ways to seriously injure yourself while doing this project. It only takes a small toolkit (jack plane, marking gauge, crosscut saw, and a large-ish chisel - 3/4" or so), but with these small pieces you might be tempted to secure them with your hands. Please do not let any body part get in front of the leading edge of your chisel.

Moving on, the first one I did in walnut turned out well. I just put some wax on the pieces for a finish. Fairham leaves you to figure out the solution to put it together yourself, which took me about a half hour. I got the impression that it was a bit loose and sloppy, as as soon as I touched it the darned thing fell apart again.

The second one (this time in cherry finished with boiled linseed oil) I chose to leave all of my cuts well inside the lines, hoping that it would cinch up tight. WRONG!

This made it even sloppier and looser, to the point that it wouldn't go together. I opened the joints up a bit, and it held together, but about like the first one. I did find out that once it is together, if you press all of the pieces together, then it stays fairly tight. Perhaps this is the way it is supposed to be.

Perhaps one of you knows the intricacies of the construction of this puzzle? In the meantime, I think I'll leave these on my desk and watch the faces of my visitors as the puzzle disintegrates as soon as they touch it.

Flattening the top of the workbench

Brian kindly let me contribute to this blog. Now please bear with me, if the grammar or the spelling isn't exactly according to rule of the English language, as my mother tongue is Danish.

As you can see on the pictures, I have started on a Roubo workbench. It will feature a wagon vise and a shoulder vise.

The shoulder vise will be mounted on the small protrusion which can be seen on the end of the workbench.

It will be made from an old shoulder vise from a scrapped bench.

The wagon vise will be made from an old book binders press.

The workbench is made from larch which was what I had in stock, so thats why it isn't made out of e.g. beech or oak.

I tried to flatten the bench top on my old bench, but the beech had been glued up so that the grain was reversing, so I couldn't make it work. Besides I hit some buried pins as well..

This benchtop has been glued up so the grain makes it easy to plane.

I used my old wooden jointer, and it was perfect for the job.

As you can see on the pictures, I have started on a Roubo workbench. It will feature a wagon vise and a shoulder vise.

The shoulder vise will be mounted on the small protrusion which can be seen on the end of the workbench.

It will be made from an old shoulder vise from a scrapped bench.

The wagon vise will be made from an old book binders press.

The workbench is made from larch which was what I had in stock, so thats why it isn't made out of e.g. beech or oak.

I tried to flatten the bench top on my old bench, but the beech had been glued up so that the grain was reversing, so I couldn't make it work. Besides I hit some buried pins as well..

This benchtop has been glued up so the grain makes it easy to plane.

I used my old wooden jointer, and it was perfect for the job.

I expect that the next step is to mount the shoulder vise.

Sunday, January 20, 2013

Woodworking Books For Sale

In an attempt to get somewhat more organized, I painfully identified a few books on my shelf that I need to part with in the interests of keeping the the house from being totally overwhelmed.

These are all good books that survived my last purge. I had to be heartless in pulling them off of my shelf, and would like to see them go to a good home.

They are all in good shape, except where noted. Payment is through PayPal, or you can mail a check, if you feel more comfortable. All prices are without shipping.

The first email that says, "I want it," gets it. To me at this email address:

I'll mail it out this week, when you get it please send the purchase price plus whatever I paid USPS for shipping.

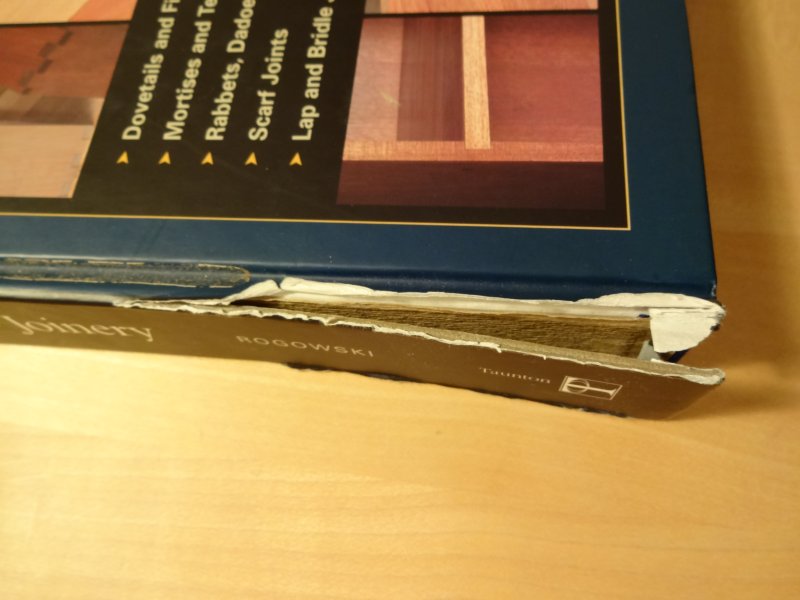

"The Complete Illustrated Guide to Joinery" by Gary Rogowski. SOLD

This book I recieved as a gift, and it took some damage in the mail getting to me (see below). The spine is torn. Good information, though, and a bargain for this book.

"The Complete Illustrated Guide to Furniture & Cabinet Construction" by Andy Rae. $20. This book has been well cared for.

"The Art of Fine Tools" by Sando Nagyszalanczy. $10. Looks like the front cover has a small bend, as seen in the photo below. This one has some awesome tool porn in it.

"Joinery Shaping & Milling (Essentials of Woodworking)" This appears to be a collection of articles from Fine Woodworking Magazine ca. 1999. $10

This book is in good shape.

"The Complete Guide to Sharpening" by Leonard Lee. SOLD

I was not able to get consistently sharp until I read this book. A fantastic treatise on real-world sharpening techniques. It is time to pass this one on to someone else who would benefit.

These are all good books that survived my last purge. I had to be heartless in pulling them off of my shelf, and would like to see them go to a good home.

They are all in good shape, except where noted. Payment is through PayPal, or you can mail a check, if you feel more comfortable. All prices are without shipping.

The first email that says, "I want it," gets it. To me at this email address:

I'll mail it out this week, when you get it please send the purchase price plus whatever I paid USPS for shipping.

"The Complete Illustrated Guide to Joinery" by Gary Rogowski. SOLD

This book I recieved as a gift, and it took some damage in the mail getting to me (see below). The spine is torn. Good information, though, and a bargain for this book.

"The Complete Illustrated Guide to Furniture & Cabinet Construction" by Andy Rae. $20. This book has been well cared for.

"The Art of Fine Tools" by Sando Nagyszalanczy. $10. Looks like the front cover has a small bend, as seen in the photo below. This one has some awesome tool porn in it.

"Joinery Shaping & Milling (Essentials of Woodworking)" This appears to be a collection of articles from Fine Woodworking Magazine ca. 1999. $10

This book is in good shape.

"The Complete Guide to Sharpening" by Leonard Lee. SOLD

I was not able to get consistently sharp until I read this book. A fantastic treatise on real-world sharpening techniques. It is time to pass this one on to someone else who would benefit.

Friday, January 18, 2013

Essential Tools for Newbies: What Tool Next? - POLL

I'll give five bucks to any avid woodworker who has all of the tools you will ever want, and the number of tools you have is less than ten.

No?

That's because once you get hooked, it is hard to avoid dreaming about how awesome it would be if you only had an -INSERT DREAM TOOL HERE- (or another one). The galoots say it is a slippery slope. Tune up a two dollar rummage sale hand saw so it works better than you could ever imagine, and all of a sudden there are dozens of old saws in your shop.

Sounds like fun, doesn't it?

If you have read the posts in my Beginner's Tool Kit series, you know which tools I advocate a beginner aqcuire first:

- Jack plane

- Ryobi saw

- Pair of bench chisels (3/8" & 3/4" or so)

- Marking and measuring tools

- Sharpening system

I have been working (and will continue to) work on a few projects using only these tools. The idea is not for you to pare your tools down to these few, but to get the right few when starting out to be able to do some actual woodwork. It is difficult to do anything useful if all you have is a plow plane and a 500 EURO hammer

The next logical step is, where do we go from here? What tool do I need next?

The answer to that question is personal. However, I have the answer:

- It depends.

What does it depend on? It depends on what you actually need for the work you do.

To the right of this post I have created a poll to see what tools you, my loyal readers, would like to see me discuss in a future post (or two). I have listed several tools that are essential for different kinds of operations. If you only had my basic hand tools, which one do you think you need next?

If I don't have a tool you think should be on the list, please let me know in the comments. Also, if you would like to share why you answered the way you did, leave a comment.

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Blog Review: Scott Berkun

If all of you woodworkers haven't heard of Scott Berkun yet, don't worry. This is not what you think.

Scott Berkun writes about writing.

So, this post is more for you woodworking bloggers out there than for those of you who want my thoughts on the latest router bits.

If you want my thoughts on the latest router bits, here they are: I plan to do all of my future moldings with hand planes. Forget the router. Fearing for my life and not being able to hear for two days is not my idea of fun.

How to Write a Book – The Short Honest Truth

His writing style is very engaging. I found myself clicking around on different posts, and came upon this video that I think may be helpful to bloggers on any subject:

It is a time lapse movie of the author writing an essay, 30X normal speed. Plus he speaks about what he is doing.

I think I might read this blog regularly, and hopefully pick up a few tips on writing. This blog seems a bit different of an approach than most of the writing courses I took in college. In other words, I think I can put these ideas to good use!

Scott Berkun writes about writing.

So, this post is more for you woodworking bloggers out there than for those of you who want my thoughts on the latest router bits.

If you want my thoughts on the latest router bits, here they are: I plan to do all of my future moldings with hand planes. Forget the router. Fearing for my life and not being able to hear for two days is not my idea of fun.

Stay on target...I was flipping through my search engine today and stumbled accross this post:

Gold Five (1977)

How to Write a Book – The Short Honest Truth

His writing style is very engaging. I found myself clicking around on different posts, and came upon this video that I think may be helpful to bloggers on any subject:

It is a time lapse movie of the author writing an essay, 30X normal speed. Plus he speaks about what he is doing.

I think I might read this blog regularly, and hopefully pick up a few tips on writing. This blog seems a bit different of an approach than most of the writing courses I took in college. In other words, I think I can put these ideas to good use!

Monday, January 14, 2013

Fun With Lap Joints - Slideshow

"My brief love affair with Japanese saws is now over."-Ben St. John after using my BadAxe dovetail saw, 2011.

I wasn't at all sure this project was going to turn out, so I didn't post about it until now, when it is done. This is another project that can be built with only the tools in my Beginner's Tool Kit. If you don't want to read my old blog posts, I think beginners can focus on just buying a few good tools and do some work with them. They include only a jack plane, a ryoba saw, two chisels (3/8" and 3/4"), a couple of marking tools and something with which to keep everything sharp.

I was amazed at how smooth this project went. There were plenty of things that could go wrong, but thankfully none did.

This mallet is my own design. At least, I have never seen one constructed like it before. Normally a laminated mallet uses three laminations. The center one is the same thickness as the handle, so it is easily sawn out and glued up.

A traditional mallet is made of a single block of wood with a mortise in the middle for the handle. Since the tools I have chosen would make that extremely difficult, I chose to build a laminated mallet.

I have been practicing lap joints, and I thought it would be fun to build a mallet with only two laminations. The lap joints taper, so the handle can not slip out (indeed, there is no glue holding it in). And for good measure, I thought one side of the lap should be dovetailed, to hold everything together even if the glue holding the lamination fails.

I chose a hunk of walnut that was rolling around in my shop, and a bit of Honduran mahogany I got a while ago for the handle.

The sliding dovetail was not as steep of an angle as I had originally envisioned. I was looking for something that would let me mark out a consistent angle that might be available to anyone, and settled on the same square that is 2 1/2 degrees off square that I made for the taper. It turns out that this was a good choice. It made things a bit easier, and it is plenty strong to hold these mallet halves together.

In the video you see me making one of the sliding dovetail cuts with a backsaw. I wouldn't have done this, except that I had loaned out my Ryoba saw to someone for a few days. I did get the saw back and used it for the other half. The BadAxe worked WAYYY better. I had a lot less paring to do to clean up this cut with the BadAxe. However, the Ryoba worked surprisingly well when crosscutting the mallet faces. I had very little planing to do to smooth the faces of the mallet.

One thing I perhaps should have put a bit more thought into was the size of this mallet. I really needed to replace my small mallet. This one is huge, and should answer nicely on a 1/2" mortising chisel. I guess I'll just have to build another.

Music: Beguine (Paniks) / CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

I wanted to give this mallet a manly name, so I discussed it with my wife. While I was trying to think of something manly like Thor, Mongo, or King Kong, she said, "How about Trevor?"

I figure it is kind of like trying to change a dog's name. Once he answers to Fifi, you can never really call him Butch.

Trevor the Mallet, it is.

See my other Beginner's Tool Kit Projects.

I wanted to give this mallet a manly name, so I discussed it with my wife. While I was trying to think of something manly like Thor, Mongo, or King Kong, she said, "How about Trevor?"

I figure it is kind of like trying to change a dog's name. Once he answers to Fifi, you can never really call him Butch.

Trevor the Mallet, it is.

See my other Beginner's Tool Kit Projects.

Sunday, January 13, 2013

How Perfect Does It Have to Be?

Like many of you, I started my woodworking hobby using machines. About six or seven years ago my wife and I renovated our spiral staircase, which included replacing the ugly carpet lining on the steps with some really nice beach planks.

I got the idea from our next door neighbor, who had her steps lined with oak. Her contractors used 18mm thick laminated wood from the home center.

The beach I bought was inexpensive (don't you wish you lived in Europe, too?) so I got plenty. The thinnest rough lumber I could get from the local lumber yard was 40 mm thick as opposed to the 18mm that the Frau and I had in mind.

What did I do? I ran all of that beautiful 6/4 roughstock through the thickness planer until I had all of the 3/4" thick material that I needed. What a waste.

What should I have done? I should have resawn those boards and flattened them with a hand plane.

Does that seem like an awful lot of work to you? It did to me. Let me tell you, all of that thickness planing was no fun either. One of the reasons I didn't do it by hand was I was having a hard time figuring out how to use a hand plane to get the two opposite faces of a board perfectly parallel, like a thickness planer would.

Since then, I have learned the secret to getting the two opposite faces of a board perfectly parallel.

The secret? Don't.

Please do not misunderstand. Good work is good work, and the pursuit of perfection is a noble cause. Also there are times where precision work on this level is required.

There are limits, however.

One of the reasons a lot of machine-made furniture looks so different than hand-made stuff is that many craftsmen know what needs to be perfect and what does not.

As an example, If I would have resawn those beach planks and smoothed both sides with a handplane without regard to how perfectly parallel the two faces of the boards were, would anyone care? Would the steps somehow look wrong? Of course not. In fact, the small differences in the steps may have given it a more charming appearance. They certainly wouldn't work any different.

One can use these ideas in many aspects of woodworking. If you are making a dovetailed box, for example, there is no rule that says anything has to be flat and square other than the inside surfaces. A drawer, on the other hand, needs to ride inside of a case, so the outside of it should be square and parallel as well.

I have spent time on my recent layout square projects to ensure my stock was perfectly six square to begin the project. I am confident that these small bits of wood turned out pretty darned accurate. For a tool like this, they need to be.

Should you spend time making every project perfect like that? No. Think about a table. The part of the apron you see should be flat and perpendicular to the top. What about the part you don't see?

Who cares? No one will ever see that part. The only reason this face should be perfect is if you are aligning things from this face for some reason.

For that matter, does the table top need to be reference-surface flat? As long as it looks nice and your beer glass will sit on it flat, you are OK.

That should be your real goal: Does it look nice?

Will a cigar smoker use a micrometer do see if your work on his humidor is accurate to within 1/1000th of an inch? No. He is going to look at it and say, "Won't I look like a badass pulling a double corona out of that!"

Do yourself a favor. Before you get too crazy about making opposite faces parallel, ask yourself if it is really required, or if having a flat face with a square edge is enough for your application.

| |

| Completed stairway renovation. |

I got the idea from our next door neighbor, who had her steps lined with oak. Her contractors used 18mm thick laminated wood from the home center.

The beach I bought was inexpensive (don't you wish you lived in Europe, too?) so I got plenty. The thinnest rough lumber I could get from the local lumber yard was 40 mm thick as opposed to the 18mm that the Frau and I had in mind.

What did I do? I ran all of that beautiful 6/4 roughstock through the thickness planer until I had all of the 3/4" thick material that I needed. What a waste.

What should I have done? I should have resawn those boards and flattened them with a hand plane.

Does that seem like an awful lot of work to you? It did to me. Let me tell you, all of that thickness planing was no fun either. One of the reasons I didn't do it by hand was I was having a hard time figuring out how to use a hand plane to get the two opposite faces of a board perfectly parallel, like a thickness planer would.

Since then, I have learned the secret to getting the two opposite faces of a board perfectly parallel.

The secret? Don't.

Please do not misunderstand. Good work is good work, and the pursuit of perfection is a noble cause. Also there are times where precision work on this level is required.

There are limits, however.

One of the reasons a lot of machine-made furniture looks so different than hand-made stuff is that many craftsmen know what needs to be perfect and what does not.

As an example, If I would have resawn those beach planks and smoothed both sides with a handplane without regard to how perfectly parallel the two faces of the boards were, would anyone care? Would the steps somehow look wrong? Of course not. In fact, the small differences in the steps may have given it a more charming appearance. They certainly wouldn't work any different.

One can use these ideas in many aspects of woodworking. If you are making a dovetailed box, for example, there is no rule that says anything has to be flat and square other than the inside surfaces. A drawer, on the other hand, needs to ride inside of a case, so the outside of it should be square and parallel as well.

I have spent time on my recent layout square projects to ensure my stock was perfectly six square to begin the project. I am confident that these small bits of wood turned out pretty darned accurate. For a tool like this, they need to be.

Should you spend time making every project perfect like that? No. Think about a table. The part of the apron you see should be flat and perpendicular to the top. What about the part you don't see?

Who cares? No one will ever see that part. The only reason this face should be perfect is if you are aligning things from this face for some reason.

For that matter, does the table top need to be reference-surface flat? As long as it looks nice and your beer glass will sit on it flat, you are OK.

That should be your real goal: Does it look nice?

Will a cigar smoker use a micrometer do see if your work on his humidor is accurate to within 1/1000th of an inch? No. He is going to look at it and say, "Won't I look like a badass pulling a double corona out of that!"

Do yourself a favor. Before you get too crazy about making opposite faces parallel, ask yourself if it is really required, or if having a flat face with a square edge is enough for your application.

Wednesday, January 9, 2013

GoPro HERO 3 - trombone

Since trombones have come up on my blog recently, I thought I would share this video that has gone viral:

OK, I know someone out there who reads this has one of these cameras, let's see what it looks like when mounted to a saw or a plane. Or, better yet, a hammer!

OK, I know someone out there who reads this has one of these cameras, let's see what it looks like when mounted to a saw or a plane. Or, better yet, a hammer!

Sunday, January 6, 2013

Square - Mark III

Perhaps you are getting tired of my repeating over and over this project.

Too bad, it's my blog!

I actually am working on my next project in my beginner's toolkit series. For this project, I needed a repeatable angle that is five or ten degrees out of square. Normally I would use my sliding bevel for this, but since it isn't in the list of tools for newbies, I decided to make one.

This one is even simpler than the others. I had a bit of oak that was around 1/4" thick, and decided to use it without cutting a mating lap in the blade. I only cut a lap joint in the mahogany stock to make the handle.

The fact that there is only one lap to cut instead of two, coupled with the fact that practicing this joint is paying off with some skill finally being acquired, I think this one has joints that look flawless. I know, there is just one joint, but still, there are no gaps anywhere on this one.

Another thing making it easy, is it is about five degrees or so out of square. Yeah, yeah, I did it on purpose so I could mark out this joint:

I eyeballed the angle of this. I actually have no idea what the angle is, but it is sufficient for the project I am working on.

Oh, one mea culpa is that I used my Bad Axe crosscut sash saw for this project, rather than the Ryoba that is in my beginner's tool kit.

The reason I used this saw is a rather amusing story. Long story short: I loaned my saw to a friend. Long story long:

The other day I was helping a friend install new flooring. When taking my tools over there, I looked for my old bent ryoba blade, but couldn't find it. "Oh, well, I'll just be careful with my good one."

While using it to cut the door frame to allow the parkett to slide under it, the saw really stopped cutting. I couldn't figure out why it was cutting so slow. After several dozen strokes, it started cutting quickly again.

When I removed the cutoff, I discovered that I sawed through a nail - lengthwise! I wish I kept that piece so I could show a picture. I never saw anything like it.

Remarkably, no teeth broke, even though I was using the fine crosscut side of the saw. I imagine that the saw is not sharp anymore. I therefore felt no trepidation in loaning that saw to my friend so he could finish his baseboards the next day.

Back on topic: This current square only took about 30 minutes to construct. It was smaller, so squaring up the lumber was easier. It seems to work great. As long as I have some scrap in my bin, I shouldn't have any problem coming up with squares in any configuration I need.

I think the secret to accurate paring with a chisel is accurate sawing. The less one has to mess with paring a shoulder or a cheek, the better.

If you haven't read about my suggested list of tools for someone starting out in hand tools, read this series.

If you would like to read about the projects I am making using only the tools in this toolkit, read about them here.

Too bad, it's my blog!

I actually am working on my next project in my beginner's toolkit series. For this project, I needed a repeatable angle that is five or ten degrees out of square. Normally I would use my sliding bevel for this, but since it isn't in the list of tools for newbies, I decided to make one.

This one is even simpler than the others. I had a bit of oak that was around 1/4" thick, and decided to use it without cutting a mating lap in the blade. I only cut a lap joint in the mahogany stock to make the handle.

|

| Even simpler design |

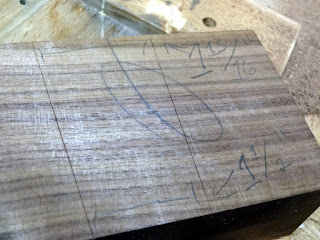

Another thing making it easy, is it is about five degrees or so out of square. Yeah, yeah, I did it on purpose so I could mark out this joint:

|

| This lap will be wider at the top than at the bottom. |

|

| Here is the new square in action. |

|

| Nice joint, eh? |

|

| Out of square - on purpose |

Oh, one mea culpa is that I used my Bad Axe crosscut sash saw for this project, rather than the Ryoba that is in my beginner's tool kit.

The reason I used this saw is a rather amusing story. Long story short: I loaned my saw to a friend. Long story long:

The other day I was helping a friend install new flooring. When taking my tools over there, I looked for my old bent ryoba blade, but couldn't find it. "Oh, well, I'll just be careful with my good one."

While using it to cut the door frame to allow the parkett to slide under it, the saw really stopped cutting. I couldn't figure out why it was cutting so slow. After several dozen strokes, it started cutting quickly again.

When I removed the cutoff, I discovered that I sawed through a nail - lengthwise! I wish I kept that piece so I could show a picture. I never saw anything like it.

Remarkably, no teeth broke, even though I was using the fine crosscut side of the saw. I imagine that the saw is not sharp anymore. I therefore felt no trepidation in loaning that saw to my friend so he could finish his baseboards the next day.

Back on topic: This current square only took about 30 minutes to construct. It was smaller, so squaring up the lumber was easier. It seems to work great. As long as I have some scrap in my bin, I shouldn't have any problem coming up with squares in any configuration I need.

I think the secret to accurate paring with a chisel is accurate sawing. The less one has to mess with paring a shoulder or a cheek, the better.

If you haven't read about my suggested list of tools for someone starting out in hand tools, read this series.

If you would like to read about the projects I am making using only the tools in this toolkit, read about them here.

Wednesday, January 2, 2013

Do Over! - Square Mark II

There were a couple problems with my first square from the last post. Namely, all those fancy chamfers that made the tool look so nice and feel so good in your hand did not allow the square to work right. Those chamfers reduced the amount of wood that register along the edge you put the tool up to. Indeed, one side doesn't grab at all. That makes this useless as a tool, and a failure as a project.

Almost.

It would be a failure if I had spent two years on this project to only find that when it is complete it didn't turn out to do what I wanted.

Instead, I spent an evening in the shop, got some good practice and figured out how to make this thing. Plus, I only am out a couple sticks of scrap.

Not sure if I should throw it out or keep it as a reminder that nobody's perfect.

So, with the information I gained in the first build fresh in my mind, I spent some more time in the shop to do it again.

Amazing! What a neat experience to be able to do this project over.

I used the exact same tool kit as the other day, i.e. my Beginner's Tool Kit. Today, my sawing was much more accurate. I remembered what I did poorly the other day and corrected the problem. As a result, the lap joint is a lot tighter than my first gappy example.

I also fixed a problem in the design. The tool didn't look right with the dimensions I had, so I made the handle longer today. I think it looks great.

Also, I finished this project in half the time. Only an hour and a half. Once again, most of the time was spent squaring up the stock.

Here is a tip that I discovered: If you want to improve your paring skills with a chisel, do a better job with your saw.

Amazingly, my shoulder cuts only needed the tiniest bit of paring. I only trimmed a little at the back of the shoulder to make the cut square (or indeed, a little undercut). One of the cheeks needed a bit of work, and some of the problems are still visible. Better luck with that next time.

I bet that if I made a dozen or so of these, my lap joint skills would be as good as I'll ever need them to be. Plus, I'll have some neat gifts for my woodworking buddies. I'll let you know how it goes.

Anyway, it was an interesting challenge doing this build with only the tools in my tool kit for beginners: a marking gauge, marking knife, square, jack plane, and two chisels (3/8" and 3/4"). Plus, my tools were sharp, and I had a hammer for adjusting the plane.

If you choose to build this square, here is what you can expect from this exercise:

Beginner - You will learn some important fundamentals with this project using the limited tool kit that you absolutely need for most every project you will build from now on. The basic skills include making rough stock six-square and lap joints. Lap joints require many of the same skills used in making tenons. Also, you will learn to saw to a line and pare with a chisel.

Veteran - You will discover if you can throw down with basic fundamental skills rather than rely on some specialty tools. Your standards are going to be high, resulting in you messing with this until it is as perfect as your patience will allow.

Either way, after adjusting the square you will have a useful tool in your kit that you can use for many years.

A note about accuracy: The closer to "square" you can make this thing during the glue-up, the better. However, it will not be perfect, and will more than likely need some adjusting. Use a pencil to draw a straight line perpendicular to the edge of a piece of scrap. Then, turn it over and draw another line starting at the same point. If you have only one line, perfect. If you have a giant "V", you have some more paring to do on the blade of the square until it gets perfect.

Once one edge makes a perfect line, either always use that edge (say, the outside edge), or also adjust the other.

Enjoy!

If you missed my series on the Beginner's Tool Kit, check it out here.

Afterthought: After planing the wood, I burnished it with my new Roubo Polissoir. This thing is awesome. All I did was rub it over the bare wood while it was dry. Everything shined up nicely. After the glue up, I applied some wax with a rag and buffed it out with a paper towel.

Almost.

It would be a failure if I had spent two years on this project to only find that when it is complete it didn't turn out to do what I wanted.

Instead, I spent an evening in the shop, got some good practice and figured out how to make this thing. Plus, I only am out a couple sticks of scrap.

|

| Mark II - Oak and Mahogany |

So, with the information I gained in the first build fresh in my mind, I spent some more time in the shop to do it again.

Amazing! What a neat experience to be able to do this project over.

I used the exact same tool kit as the other day, i.e. my Beginner's Tool Kit. Today, my sawing was much more accurate. I remembered what I did poorly the other day and corrected the problem. As a result, the lap joint is a lot tighter than my first gappy example.

I also fixed a problem in the design. The tool didn't look right with the dimensions I had, so I made the handle longer today. I think it looks great.

|

| Before and After |

Here is a tip that I discovered: If you want to improve your paring skills with a chisel, do a better job with your saw.

Amazingly, my shoulder cuts only needed the tiniest bit of paring. I only trimmed a little at the back of the shoulder to make the cut square (or indeed, a little undercut). One of the cheeks needed a bit of work, and some of the problems are still visible. Better luck with that next time.

|

| I think it is Not Too Shabby |

Anyway, it was an interesting challenge doing this build with only the tools in my tool kit for beginners: a marking gauge, marking knife, square, jack plane, and two chisels (3/8" and 3/4"). Plus, my tools were sharp, and I had a hammer for adjusting the plane.

If you choose to build this square, here is what you can expect from this exercise:

Beginner - You will learn some important fundamentals with this project using the limited tool kit that you absolutely need for most every project you will build from now on. The basic skills include making rough stock six-square and lap joints. Lap joints require many of the same skills used in making tenons. Also, you will learn to saw to a line and pare with a chisel.

Veteran - You will discover if you can throw down with basic fundamental skills rather than rely on some specialty tools. Your standards are going to be high, resulting in you messing with this until it is as perfect as your patience will allow.

Either way, after adjusting the square you will have a useful tool in your kit that you can use for many years.

A note about accuracy: The closer to "square" you can make this thing during the glue-up, the better. However, it will not be perfect, and will more than likely need some adjusting. Use a pencil to draw a straight line perpendicular to the edge of a piece of scrap. Then, turn it over and draw another line starting at the same point. If you have only one line, perfect. If you have a giant "V", you have some more paring to do on the blade of the square until it gets perfect.

Once one edge makes a perfect line, either always use that edge (say, the outside edge), or also adjust the other.

Enjoy!

If you missed my series on the Beginner's Tool Kit, check it out here.

Afterthought: After planing the wood, I burnished it with my new Roubo Polissoir. This thing is awesome. All I did was rub it over the bare wood while it was dry. Everything shined up nicely. After the glue up, I applied some wax with a rag and buffed it out with a paper towel.

Tuesday, January 1, 2013

Basic Tool Kit Project - Square

I decided one can only go so long writing about woodworking without actually doing any. To put my money where my mouth is, I designed and constructed a square and used only the tools in my Beginner's Tool Kit.

It's not too pretty, but here is my prototype:

If you want to see all of the gory details, check out the slideshow.

You really need a square in your basic tool kit. The size of this square isn't all that critical (mine is around nine inches long and 4 1/2" wide).

I chose lap joints because my basic tool kit doesn't have a chisel narrower than 3/8" yet. The lap joint should be plenty strong for this. Besides, if it comes apart, you can easily make another one.

Construction is pretty straight forward, just lap joints and perhaps some chamfering if you so desire. The idea is that the handle is thicker than the blade, so you can push the handle up to your true edge and mark with your pencil or knife along the blade.

In retrospect, I recommend not going chamfer-happy like I did. You'll notice that there is a nice pretty chamfer that makes it comfy to hold like a pistol (indeed, when I showed it to my wife, she shot me with it). However, it may reduce its accuracy if it slips on the work you are trying to mark square.

I also don't think having the joint off-set looks as nice here as it might on one with a bridle joint. Not to fear, this only took a couple hours to make, mostly because I was being anal about squaring my stock.

Stay tuned for Mark II.

Music: No Money No Honey All We Got Is Us (The Underscore Orkestra) / CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

It's not too pretty, but here is my prototype:

| The very first Beginner's Tool Kit Square. |

I chose lap joints because my basic tool kit doesn't have a chisel narrower than 3/8" yet. The lap joint should be plenty strong for this. Besides, if it comes apart, you can easily make another one.

Construction is pretty straight forward, just lap joints and perhaps some chamfering if you so desire. The idea is that the handle is thicker than the blade, so you can push the handle up to your true edge and mark with your pencil or knife along the blade.

In retrospect, I recommend not going chamfer-happy like I did. You'll notice that there is a nice pretty chamfer that makes it comfy to hold like a pistol (indeed, when I showed it to my wife, she shot me with it). However, it may reduce its accuracy if it slips on the work you are trying to mark square.

I also don't think having the joint off-set looks as nice here as it might on one with a bridle joint. Not to fear, this only took a couple hours to make, mostly because I was being anal about squaring my stock.

Stay tuned for Mark II.

Music: No Money No Honey All We Got Is Us (The Underscore Orkestra) / CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)